The term “queer” as an adjective can be defined as strange or odd from a conventional viewpoint, unusually different, singular, suspicious, shady, and to be of a questionable nature or character. All of these definitions share the connotation of difference, that to be queer is to be something other than normal. As such, the term has been appropriated by heteronormative culture as a slang term for homosexuals. This use of the term as slang is abusive in nature, but this abuse and conflict is utilized by queer theory. In Judith Butler’s "Critically Queer" she says, “The term ‘queer’ has operated as one linguistic practice whose purpose has been the shaming of the subject it names or, rather, the producing of a subject through that shaming interpellation. ‘Queer’ derives its force precisely through the repeated invocation by which it has become linked to accusation, pathologization, insult.” In comparison to Lesbian and Gay Criticism (which in its name is placed in an identity category, the politics of which are an issue for Judith Butler and queer theory in general) queer theory uses the opposition to and in the term “queer” to provide agency in the analysis of anything that deviates from heterosexual norms as well as the potential of queering subjects. To queer is to reveal curiosity or queerness, as evident by Shakesqueer, which examines Shakespearean works to reveal queer elements in its themes and characters. Queer theory, unlike lesbian feminism as explained by Barry, is not woman centered, nor man centered, and rejects female separatism through the awareness of the similar political and social interests of both gay men and lesbians and anyone that has become a subject of the queer stigma through the shaming interpellation.

Inherent in queer theory is an issue surrounding identity politics. Complicated in nature, the issue lies in identifying with a particular identity while simultaneously rejecting identity politics. Identification in itself is complicated by the relationship between gender and sexuality, and the utilization of a particular identity for political reasons is complicated by the notion of performance of both gender and sexuality.

Butler's example, in "Imitation and Gender Insubordination," is that sexuality as part of the unconscious is complicated by attempts at transparent sexuality (through "coming out") which may cease sexuality's existence as sexuality. Being out relies on being in, and in a heteronormative society, sexuality is always assumed to be hidden. By coming out, a person reveals their sexuality, but the other that they come out to does not know the meaning or implications of that sexuality, and the subject is once again put in a position of scrutiny and Otherness. Through coming out there is a constant deferral of meaning, but it is only sexuality that does not conform to the norm that must come out and endlessly defer a signified. Since sexuality can mean and manifest in a multitude of ways, there is no way to define or name sexuality without placing the person in the queer subject position and therefore back in the closet. Identity through sexuality means a perpetually queer subject position. Butler cites the instability of identity categories in relation to sexuality, and it is the instability of these categories that appeals to her through pleasure derived by transgressing them. Through transgression and the constant shifting of meaning, sexuality and identity can be utilized to deconstruct heteronormativity. Butler argues that drag helps to illustrate that all gender is a performance, and by choosing to identify and thereby perform as a lesbian while simultaneously being a lesbian, there is a repetition of the "I," which constitutes and contests the coherence of that "I." If there is a lack of coherence in an identity produced by repeated performances, then the assumption of an identity for political reasons illustrates that there is instability in identity politics. Then, it can be argued, that by identifying with a particular identity the instability of identity categories can be revealed and identity politics can be rejected.

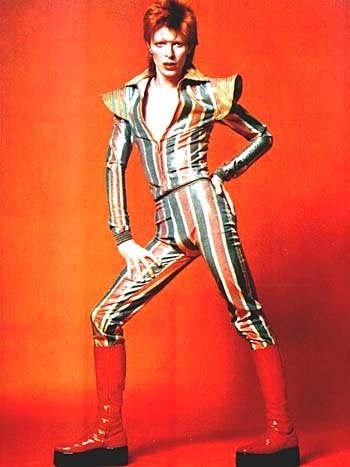

An example of the transgression of identity categories can be seen in David Bowie (and a nod must go to The Pedagogical Imperative for a bit of inspiration). In his many media incarnations (Ziggy Stardust, the Man Who Fell to Earth, The Thin White Duke, an accused Nazi, a Goblin King in love with Jennifer Connelly in Labyrinth), Bowie continually transgresses heteronormative views of sexuality and gender. He identifies as a straight man (and he has been identified by others as a bisexual, lest we forget his alleged liasons with Mick Jagger), but his performance of sexuality is not essential to his identity. He rejects the notion that his sexuality defines him (thereby rejecting identity politics), and this allows for ambiguity and a certain androgyny.

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

Feminism

believe strongly in the teachings of Derrida, post structuralism, and share similar

views on gender and sexuality. These two women may seem as though they share a

lot in common but they are both very different in the ways they discuss

feminism.

Butler is also informed by deconstruction and the difference of gender and sexuality. Butler uses the theory of iteration in terms of gender performance. She discusses binaries through analyzing the unequal power structure and social construct. She goes on to discuss drag and how it disrupts the binary but does not dissolve it. She believes in the performance of heterosexuality and thinks about sexuality in a new way. Butler theorizes performance in a rational and traditional form. She believes in feminism in the 3rd wave form. Her style of writing is unlike Cixous. Butler takes the time to fully explain what she’s writing about and does it with easy. Her writing is more in an academic essay form so following it is much more useful.

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

Bad Ass Baudrillard

Ken Rufo says that Baudrillard was his first great theorist love, and it is easy to understand why. Baudrillard did everything a theorist ought to. He read other theorists, was informed by them, contradicted them, developed his own theories, and ignited controversy with his theories. He made people think, and isn't that the point of critical theory, to provide analysis that provokes thought and further analysis on the part of both the reader and the theorist? Rufo provides a history of Baudrillard's work, and in doing so outlines several points that (at least for this reader) spurred contemplation.

First, Rufo explains that Baudrillard began as a Marxist, and through his analysis turned Marxism inside out. Baudrillard began by incorporating sign-value into structural Marxism, and the focus on sign-value meant a focus on consumption rather than production. Rufo's example, Tommy Hillfiger's logo on polo shirts made in sweat shops, illustrates that commodities are completely removed from their production. What is important is that those clothes have the Tommy Hillfiger logo on them, and that people will pay a lot of money for that logo. By focusing on the sign-value of Tommy Hillfiger's logo and the revenue it generates, the production of the clothing is forgotten, it doesn't matter.

Baudrillard later, as Rufo explains, complicated this by positing sign-value as something that enabled the analysis of commodity in the first place. He argues that it is integral to the necessary pre-existing understanding of language for Marxist criticism. This enables the connection to Saussure and semiotics. To justify this relationship, Baudrillard (and Rufo) point to the sign, signifier, and signified, and Marxist commodity. The sign is comprised of the signifier and signified, and the commodity, and it's sign-value, is comprised of use-value and exchange-value. The relationship of the sign-value of the commodity to its use-value and exchange-value, is necessarily arbitrary, like the relationship of the sign to the signifier and signified.

This correlation, Rufo argues, allowed Baudrillard to arrive at the conclusion that systems of analysis are simply new systems of exchange-values. The consequence of this is that theories produce self-fulfilling prophecies. By developing terms to suit analysis, theorists cultivate concepts that justify their theories. This creates a sort of model for critical theory, which Rufo explains as a way of following the analytical formula and utilizing terms and concepts specifically designed to prove the theory in order to validate it. Baudrillard's criticism of other theorists, like Lacan and Foucault, relates to his earliest works on simulation. This model for critical theory enables the construction of artificial meanings that appear to be "real" meanings. In doing so, the theories pretend to find insight, when they actually simulate insight by creating the means with which they find it. Baudrillard's criticism of Psychoanalysis is that it allegedly claims to have discovered the unconscious, but it actually constructs and produces it as a tool in support of Psychoanalysis. Essentially, theory is constantly producing systems that claim to discover when they actually produce. What is important in theory is the insights it is thought to provide, not the process by which they are developed or constructed.

This simulation of meanings in theory is related to Baudrillard's work with simulation and media, and his argument that the media produces an artificial reality as theory creates artificial meanings. The media, especially television according to Baudrillard, creates and copies things which the general population comes to accept as real. Baudrillard outlines the four orders of simulation: the first, in which simulation stands in for reality, the second, in which simulation hides the lack of reality, the third, in which simulation produces its own reality, and the fourth, in which simulation is so pervasive that it is everywhere, encompassing everything and nothing all at once. He revised the third order before introducing the fourth, and it can be understood as the simulacrul stage in which the copy no longer has an original.

In calling the third order of simulation as the simulacral stage, Baudrillard is borrowing the term simulacrum from Plato, effectively reappropriating the term to suit his needs. This perhaps seems contradictory to Baudrillard's criticism of theory itself, as he is producing concepts and terms to validate his own theory. But isn't this contradiction a larger problem in theory? Or is it a point of theory? Each branch of theory has its own contradictions and conflicts, which the subsequent reactionary theories seek to challenge and further complicate. Structuralism argues that language is a stable system of differences, with binary divisions and opposites that never confront one another. Post Structuralism recognizes language as unstable, and argues that the binaries are in constant conflict. New theories arise in opposition to old theories, and are constantly replacing one another as the dominant theory. Baudrillard likely recognized his own contradictions (at least Ken Rufo does), and these contradictions lay the groundwork for reactionary theory.

In his later work, Baudrillard addresses the Impossible Exchange Barrier, which suggests that the world is resistant to attempts of theorizing it. Theories reach a certain point at which they can no longer address the entirety of their opposition without contradiction. In light of his theories of simulation and simulacrum, this may be a good thing according to Rufo, in that this obstacle might thwart the imposition of value-meanings.

Rufo closes his crash course on Baudrillard with the idea that Baudrillard was not trying to rescue the real, but rather rescue illusion, which cannot happen in a world in which everything is "realized." A world where there is no reality other than a simulation that has created its own meaning is precisely where we are today. If everything is a simulation to the point where it becomes reality, then there is no possibility of mystery or illusion, because the simulation and reality are part of a grand illusion, which is a theoretical quarrel. Baudrillard's work, according to Rufo, attempts to reproduce illusion and mystery, and to avoid the traps that plague critical theory.

Right on, Baudrillard.

First, Rufo explains that Baudrillard began as a Marxist, and through his analysis turned Marxism inside out. Baudrillard began by incorporating sign-value into structural Marxism, and the focus on sign-value meant a focus on consumption rather than production. Rufo's example, Tommy Hillfiger's logo on polo shirts made in sweat shops, illustrates that commodities are completely removed from their production. What is important is that those clothes have the Tommy Hillfiger logo on them, and that people will pay a lot of money for that logo. By focusing on the sign-value of Tommy Hillfiger's logo and the revenue it generates, the production of the clothing is forgotten, it doesn't matter.

Baudrillard later, as Rufo explains, complicated this by positing sign-value as something that enabled the analysis of commodity in the first place. He argues that it is integral to the necessary pre-existing understanding of language for Marxist criticism. This enables the connection to Saussure and semiotics. To justify this relationship, Baudrillard (and Rufo) point to the sign, signifier, and signified, and Marxist commodity. The sign is comprised of the signifier and signified, and the commodity, and it's sign-value, is comprised of use-value and exchange-value. The relationship of the sign-value of the commodity to its use-value and exchange-value, is necessarily arbitrary, like the relationship of the sign to the signifier and signified.

This correlation, Rufo argues, allowed Baudrillard to arrive at the conclusion that systems of analysis are simply new systems of exchange-values. The consequence of this is that theories produce self-fulfilling prophecies. By developing terms to suit analysis, theorists cultivate concepts that justify their theories. This creates a sort of model for critical theory, which Rufo explains as a way of following the analytical formula and utilizing terms and concepts specifically designed to prove the theory in order to validate it. Baudrillard's criticism of other theorists, like Lacan and Foucault, relates to his earliest works on simulation. This model for critical theory enables the construction of artificial meanings that appear to be "real" meanings. In doing so, the theories pretend to find insight, when they actually simulate insight by creating the means with which they find it. Baudrillard's criticism of Psychoanalysis is that it allegedly claims to have discovered the unconscious, but it actually constructs and produces it as a tool in support of Psychoanalysis. Essentially, theory is constantly producing systems that claim to discover when they actually produce. What is important in theory is the insights it is thought to provide, not the process by which they are developed or constructed.

This simulation of meanings in theory is related to Baudrillard's work with simulation and media, and his argument that the media produces an artificial reality as theory creates artificial meanings. The media, especially television according to Baudrillard, creates and copies things which the general population comes to accept as real. Baudrillard outlines the four orders of simulation: the first, in which simulation stands in for reality, the second, in which simulation hides the lack of reality, the third, in which simulation produces its own reality, and the fourth, in which simulation is so pervasive that it is everywhere, encompassing everything and nothing all at once. He revised the third order before introducing the fourth, and it can be understood as the simulacrul stage in which the copy no longer has an original.

In calling the third order of simulation as the simulacral stage, Baudrillard is borrowing the term simulacrum from Plato, effectively reappropriating the term to suit his needs. This perhaps seems contradictory to Baudrillard's criticism of theory itself, as he is producing concepts and terms to validate his own theory. But isn't this contradiction a larger problem in theory? Or is it a point of theory? Each branch of theory has its own contradictions and conflicts, which the subsequent reactionary theories seek to challenge and further complicate. Structuralism argues that language is a stable system of differences, with binary divisions and opposites that never confront one another. Post Structuralism recognizes language as unstable, and argues that the binaries are in constant conflict. New theories arise in opposition to old theories, and are constantly replacing one another as the dominant theory. Baudrillard likely recognized his own contradictions (at least Ken Rufo does), and these contradictions lay the groundwork for reactionary theory.

In his later work, Baudrillard addresses the Impossible Exchange Barrier, which suggests that the world is resistant to attempts of theorizing it. Theories reach a certain point at which they can no longer address the entirety of their opposition without contradiction. In light of his theories of simulation and simulacrum, this may be a good thing according to Rufo, in that this obstacle might thwart the imposition of value-meanings.

Rufo closes his crash course on Baudrillard with the idea that Baudrillard was not trying to rescue the real, but rather rescue illusion, which cannot happen in a world in which everything is "realized." A world where there is no reality other than a simulation that has created its own meaning is precisely where we are today. If everything is a simulation to the point where it becomes reality, then there is no possibility of mystery or illusion, because the simulation and reality are part of a grand illusion, which is a theoretical quarrel. Baudrillard's work, according to Rufo, attempts to reproduce illusion and mystery, and to avoid the traps that plague critical theory.

Right on, Baudrillard.

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

"There is no language in a heap of stones."

For our response, we read an interview of Jack Kerouac conducted by Ted Berrigan. It can be found here: http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4260/the-art-of-fiction-no-41-jack-kerouac

It’s difficult to conceive of Jack Kerouac, the author, without considering Jack Kerouac, the individual. So influential were his own experiences in his work that Kerouac lamented the interview process, asking why he must waste his breath answering hundreds of questions when he has spent his entire career “interviewing myself in my novels.” However, Kerouac is often viewed not as an individual writer, but as the representative, or spokesperson, for a group he named: the Beat Generation. Kerouac coined this phrase in 1948 in a conversation with his close friend and fellow Beat writer, John Clellon Holmes. The group also included influential writers Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, William S. Burroughs, and Gregory Curso. Though each of these men made significant contributions to American literature, they are often considered as a unit, rather than autonomously. In this way, the Beat Generation, particularly Jack Kerouac, represents a conflation of the individual writer and the author. Kerouac, as his interview with Ted Berrigan indicates, refuses to play the role of a writer who is somehow separate or removed from his work, instead attempting to get closer to actual lived experience and forms of thought through his prose.

The connection between Kerouac’s “spontaneous style” of prose and his erratic manner erratic manner of speaking cannot be ignored in his interview with Ted Berrigan. Kerouac resists the formal method of interview at all levels: he frequently interrupts the interview, suspends conversation to recite poetry for long portions of the tape, and speaks on subjects that have little or no connection to the question being asked of him. While some of these factors may be due to the fact that all participants in this interview are in various states of drunkenness and have consumed at least three kinds of pills during the course of the interview, it is clear by Kerouac’s responses that he is not interested in maintaining any kind of false pretense during the interview process. Kerouac’s frequent interruptions and tangents call attention to the Beat philosophy to which he adheres: the idea that one should attempt to get as close as possible to actual lived experience and though through speech and writing. Kerouac often corrects Berrigan, making additions or amendments to his questions and comments. This self-conscious need to correct Berrigan’s speech calls attention to the superficiality of the interview process and the inadequacy of language.

Despite the problems of language, which are likely compounded by the mixture of prescription drugs and alcohol consumed by all parties, readers can gain some insight regarding Kerouac’s take on his generation and his writing. The circumstances surrounding this interview and the atmosphere in which it takes place are interesting in and of themselves. First, Berrigan’s introduction notes that the Kerouac’s do not have a telephone, so the interviewing crew simply shows up on Kerouac’s doorstep one day when they feel it’s time to talk. Kerouac’s wife, Stella, answers the door and initially refuses to let the interviewers in, thinking they are simply another hoard of people looking for the author of On the Road. Berrigan brings two friends with him to the interview, poets Aram Saroyan and Duncan McNaughton. Thus, rather than a standard two-person, question-and-answer style interview, readers get a myriad of six different voices all conversing, drinking, and reciting poetry. This atypical style of interviewing speaks to both the perception of Kerouac as a writer and the connection between the author and the man. In fact, the confusion and spontaneity of Berrigan and Kerouac’s initial meeting calls to mind several scenes in on the Road, particularly the moment when Sal shows up with Dean and a hoard of friends at his Aunt’s: all are reluctantly ushered in, fed, and entertained, but always with the understanding that their welcome is conditional, and they may only stay so long.

In addition, the long and abstract responses Kerouac gives to Berrigan’s questions draw a parallel between the style of his prose and his manner of speaking. Throughout the interview process, Kerouac seems suspicious of Berrigan, refusing to be subjected to the authority of the interviewer over the interviewee. As mentioned before, Kerouac often answers circuitously, or turns the question on Berrigan, exploring the meaning and reasons behind asking such a thing, rather than answering directly. The vast majority of the interview focuses on the connection between Kerouac’s life and his work, seemingly drawing the conclusion the Beat literature is more a group effort, rather than a collection of works promulgated by individuals. For example, Berrigan discusses Kerouac’s role in the production of William S. Burrough’s Naked Lunch and spend a lot of time discussing Ginsberg’s influence in Kerouac’s work. In this way, the interviewer seems to suggest that there is no difference between the characters and style in Beat literature and the lives of the men who were considered Beat. This assumption is often made, so much so that scholars often hyphenate names, referring to Neal Cassidy as Moriarty-Cassidy. It would be interesting (though inconsequential) to consider how this assumption informed both Kerouac’s writing of these characters, and also, given the level of interaction these writer had with each other, how Kerouac’s interpretation of these men affected their actual relationships and actions.

Kerouac pays particular attention to the idea of what it means to be a great writer and how this status has both informed as affected his career as a writer. In the end, he says that “Notoriety and public confession in the literary form is a frazzler of the heart you were born with, believe me,” which is to suggest that publication, not writing, is what makes an author, and in the end, perverts the writer. Towards the end of the interview, Kerouac stops Berrigan, saying there is something important he needs to say before the tape ends. This vital piece Kerouac must includes a meditation on his name. He explains how etymology of his name means many different things, but that ultimately the name Kerouac means “There is no language in a heap of stones."

Whether Kerouac and the Beat writers were actually successful in their attempts to convey something authentic about experience and thought is open to interpretation. What the name or the man Kerouac actually represents is beyond the scope of this project. However, it is clear from his interview with Berrigan that Kerouac, at least the man, believed in the power of language to immortalized his heroes and to question our assumptions. In this way, Kerouac has left at some bit of himself immortalized in his prose, and while the influence of his writing may be something entirely separate from the man who wrote it, Kerouac can at least be credited with naming a discourse, if not fathering one.

It’s difficult to conceive of Jack Kerouac, the author, without considering Jack Kerouac, the individual. So influential were his own experiences in his work that Kerouac lamented the interview process, asking why he must waste his breath answering hundreds of questions when he has spent his entire career “interviewing myself in my novels.” However, Kerouac is often viewed not as an individual writer, but as the representative, or spokesperson, for a group he named: the Beat Generation. Kerouac coined this phrase in 1948 in a conversation with his close friend and fellow Beat writer, John Clellon Holmes. The group also included influential writers Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, William S. Burroughs, and Gregory Curso. Though each of these men made significant contributions to American literature, they are often considered as a unit, rather than autonomously. In this way, the Beat Generation, particularly Jack Kerouac, represents a conflation of the individual writer and the author. Kerouac, as his interview with Ted Berrigan indicates, refuses to play the role of a writer who is somehow separate or removed from his work, instead attempting to get closer to actual lived experience and forms of thought through his prose.

The connection between Kerouac’s “spontaneous style” of prose and his erratic manner erratic manner of speaking cannot be ignored in his interview with Ted Berrigan. Kerouac resists the formal method of interview at all levels: he frequently interrupts the interview, suspends conversation to recite poetry for long portions of the tape, and speaks on subjects that have little or no connection to the question being asked of him. While some of these factors may be due to the fact that all participants in this interview are in various states of drunkenness and have consumed at least three kinds of pills during the course of the interview, it is clear by Kerouac’s responses that he is not interested in maintaining any kind of false pretense during the interview process. Kerouac’s frequent interruptions and tangents call attention to the Beat philosophy to which he adheres: the idea that one should attempt to get as close as possible to actual lived experience and though through speech and writing. Kerouac often corrects Berrigan, making additions or amendments to his questions and comments. This self-conscious need to correct Berrigan’s speech calls attention to the superficiality of the interview process and the inadequacy of language.

Despite the problems of language, which are likely compounded by the mixture of prescription drugs and alcohol consumed by all parties, readers can gain some insight regarding Kerouac’s take on his generation and his writing. The circumstances surrounding this interview and the atmosphere in which it takes place are interesting in and of themselves. First, Berrigan’s introduction notes that the Kerouac’s do not have a telephone, so the interviewing crew simply shows up on Kerouac’s doorstep one day when they feel it’s time to talk. Kerouac’s wife, Stella, answers the door and initially refuses to let the interviewers in, thinking they are simply another hoard of people looking for the author of On the Road. Berrigan brings two friends with him to the interview, poets Aram Saroyan and Duncan McNaughton. Thus, rather than a standard two-person, question-and-answer style interview, readers get a myriad of six different voices all conversing, drinking, and reciting poetry. This atypical style of interviewing speaks to both the perception of Kerouac as a writer and the connection between the author and the man. In fact, the confusion and spontaneity of Berrigan and Kerouac’s initial meeting calls to mind several scenes in on the Road, particularly the moment when Sal shows up with Dean and a hoard of friends at his Aunt’s: all are reluctantly ushered in, fed, and entertained, but always with the understanding that their welcome is conditional, and they may only stay so long.

In addition, the long and abstract responses Kerouac gives to Berrigan’s questions draw a parallel between the style of his prose and his manner of speaking. Throughout the interview process, Kerouac seems suspicious of Berrigan, refusing to be subjected to the authority of the interviewer over the interviewee. As mentioned before, Kerouac often answers circuitously, or turns the question on Berrigan, exploring the meaning and reasons behind asking such a thing, rather than answering directly. The vast majority of the interview focuses on the connection between Kerouac’s life and his work, seemingly drawing the conclusion the Beat literature is more a group effort, rather than a collection of works promulgated by individuals. For example, Berrigan discusses Kerouac’s role in the production of William S. Burrough’s Naked Lunch and spend a lot of time discussing Ginsberg’s influence in Kerouac’s work. In this way, the interviewer seems to suggest that there is no difference between the characters and style in Beat literature and the lives of the men who were considered Beat. This assumption is often made, so much so that scholars often hyphenate names, referring to Neal Cassidy as Moriarty-Cassidy. It would be interesting (though inconsequential) to consider how this assumption informed both Kerouac’s writing of these characters, and also, given the level of interaction these writer had with each other, how Kerouac’s interpretation of these men affected their actual relationships and actions.

Kerouac pays particular attention to the idea of what it means to be a great writer and how this status has both informed as affected his career as a writer. In the end, he says that “Notoriety and public confession in the literary form is a frazzler of the heart you were born with, believe me,” which is to suggest that publication, not writing, is what makes an author, and in the end, perverts the writer. Towards the end of the interview, Kerouac stops Berrigan, saying there is something important he needs to say before the tape ends. This vital piece Kerouac must includes a meditation on his name. He explains how etymology of his name means many different things, but that ultimately the name Kerouac means “There is no language in a heap of stones."

Whether Kerouac and the Beat writers were actually successful in their attempts to convey something authentic about experience and thought is open to interpretation. What the name or the man Kerouac actually represents is beyond the scope of this project. However, it is clear from his interview with Berrigan that Kerouac, at least the man, believed in the power of language to immortalized his heroes and to question our assumptions. In this way, Kerouac has left at some bit of himself immortalized in his prose, and while the influence of his writing may be something entirely separate from the man who wrote it, Kerouac can at least be credited with naming a discourse, if not fathering one.

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

"WHERE THE FUCK IS THE BACTINE!!"

In her extremely detailed and lucid guest post, Shelden explores Lacan’s metonymic model of desire, which suggests that we can never access the object of our desire, the objet petit a. As Shelden states, “in desire, one always only approaches the object of desire but never quite reaches it. Or, if you do finally get the object of your desire, the boy or girl or iPhone of your dreams, you will inevitably find that the thing or person you thought you wanted turns out to be not as good as you thought.” Thus, one is forced to keep desiring and chasing what one believes will fill the void constituted by the system of the Symbolic, and as we all know, completely satisfying this void is impossible. We have all been in a situation when we’ve achieved something we’ve desired for a long time, and our desire for the item ends up unsatisfied. This got me thinking: what if we could fill this void? If we were capable of fulfilling every desire we could possibly construct for ourselves, what would life be like?

One of my favorite comic books, Johnny the Homicidal Maniac, showed what this impossibility would look like. In JtHM #6, Johnny accidentally kills himself and, through a clerical error, goes to heaven for a brief time. In heaven, everybody is seen sitting perfectly motionless and apparently tranquil. Johnny asks his heavenly tour guide (Damned Elise) for an explanation as to why nobody is doing anything, and she replies that the souls in Heaven do not desire anything. They feel perfectly fulfilled, and thus do not NEED to do anything, hence the sitting. Damned Elise also explains that one’s entrance to heaven imbues one with the psychic power to explode the heads of others, a talent which Johnny discovers is great fun and leads to his expulsion from heaven. If it were possible to truly feel fulfilled, we would simply sit around not feeling the desire for anything. This could only happen until one felt hungry or sleepy. Without the desire to eat or to sleep, one would die. Thus, without the search to fulfill one’s desire, one cannot live (hence the French ‘le petit mort,’ or ‘little death’).

Although an orgasm is certainly an effective tool for destroying one’s sense of self, it is not the only physical outlet which directs human subjects away from Symbolic and Imaginary coherence. Extreme physical pain performs this same task just as effectively, if not more so based on the potential for long periods of extreme pain. Generally speaking, an orgasm lasts for a maximum of 60 seconds, and usually hovers somewhere around 15 to 20 seconds. An orgasm is also sought after by most sexually active people during sexual activity. It is considered the ultimate merge with, and connection to, a partner. Pain, on the other hand, is the ultimate separation of partners. In an instance where somebody is inflicting pain upon another, there is no positive emotional connection between the two. Extreme pain is not sought after by most people (and when I say extreme pain, I mean blinding, white-hot, speechless, world-crushing pain), and has no established time frame (as opposed to the limitations of an orgasm’s lifespan).

During a period of extreme pain (such as, for example, the first moment of a bad burn), one cannot bring to mind any facts about one’s own life or. This is so because pain erases one’s sense of self, or as Shelden states, ”You are no longer thinking about what you need to do, who you think you are, or even where you are.” Of course, Shelden is referring to an orgasm’s power to make one “forget the world for the sake of sexual release.” I assume she is referring to a truly intense, genuine, volcanically hot orgasm, as opposed to a faked or ‘performed’ orgasm. Perhaps this relationship between an orgasm and physical pain is the seed behind the oft-referenced ‘fine line between pleasure and pain.’

Shelden’s post delves into the concepts of desire and sexual satisfaction. What, then, is the relationship between desire and pleasure? It is assumed that, upon fulfilling one’s desire, one attains pleasure from whatever it is that has fulfilled one’s desire. However, according to Shelden (and Lacan), the pleasure from fulfilling desire is impossible to achieve due to the impossibility of fulfilling desire in the first place. Any pleasure from supposedly fulfilling one’s desire is temporary, and thus the desire was never fulfilled in the first place. Lacan posits that “the inability to be satisfied by the object of desire maintains the lack in the subject, a void that can never be filled.” Does it follow, then, that the only possible pleasure which can truly be achieved is through the act of an orgasm? If one’s desire can never be fulfilled, then the pleasure of fulfillment is a myth. An orgasm, one’s “petit mort,” temporarily destroys the sense of self through intense pleasure. Is this form of pleasure the only genuine pleasure we can achieve?

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

A Reading of the Film "Derrida"

There is definitely irony in trying to capture the “true” Derrida in a documentary film because everything about it is fake. A documentary cannot truly capture the rawness of a person simply because a real person isn’t used to a camera. When a camera is presented in

front of you, you tend to censor your true self because of your awareness of it.

I believe the directors are aware of this because of Derrida’s comment about

how he presents a cleaned up version of himself in front of them instead of

staying in his pajamas all day which he usually does. A documentary is a lot

like an elementary school photo. The photo is used to capture the moment of

your youth so years down the road you can look at it and remember times of your

youth and what you looked like. Yet the photo does not capture the truth of who

you were back then because your given the date of the photo your mother combs

your hair a special way and makes you wear a dress or bow tie but does that really

capture the truth of your youth? No. It captures a moment in time where you’re

your cleaned up self smiling for a picture that captures nothing real or true

about who you are. The directors know this and do not try to make the film into

something it’s not. The directors are just as essential as Derrida is. They become

a part of the film because Derrida doesn’t try to pretend they are not there.

front of you, you tend to censor your true self because of your awareness of it.

I believe the directors are aware of this because of Derrida’s comment about

how he presents a cleaned up version of himself in front of them instead of

staying in his pajamas all day which he usually does. A documentary is a lot

like an elementary school photo. The photo is used to capture the moment of

your youth so years down the road you can look at it and remember times of your

youth and what you looked like. Yet the photo does not capture the truth of who

you were back then because your given the date of the photo your mother combs

your hair a special way and makes you wear a dress or bow tie but does that really

capture the truth of your youth? No. It captures a moment in time where you’re

your cleaned up self smiling for a picture that captures nothing real or true

about who you are. The directors know this and do not try to make the film into

something it’s not. The directors are just as essential as Derrida is. They become

a part of the film because Derrida doesn’t try to pretend they are not there.

Derrida is depicted through image because most of the documentary is centering upon his

image. His image is whatever he feels that day. Some days he seems apprehensive

where other days he is happier to share the inside workings of his mind. Another way of looking at his image is through the self portrait oil painting in the museum. He is asked to look at himself causes him to become anxious. The images of himself conflict because of how

different people see him. He cannot depict himself through image because like

he states in the film one cannot see how you look, it is others who see you

better.

image. His image is whatever he feels that day. Some days he seems apprehensive

where other days he is happier to share the inside workings of his mind. Another way of looking at his image is through the self portrait oil painting in the museum. He is asked to look at himself causes him to become anxious. The images of himself conflict because of how

different people see him. He cannot depict himself through image because like

he states in the film one cannot see how you look, it is others who see you

better.

Throughout the interview process Derrida does seem uneasy but it’s understandable, and this makes him easy to relate to and a likable figure. I think if he went into the interview process and spit out answers instead of quietly collecting himself before hand it would have made him look pompous. Every answer he gives is well thought out and intriguing. There is some disconnection in the interview but I think it’s only because of Derrida's brilliancy. When asked the question about love he shows a hesitance only because he’s being honest and

cannot answer the question the way the interviewer asks it. After the

interviewer rewords it, Derrida gives yet another brilliant answer and makes

the interview a success. If there wasn’t any disconnect it would seem too

practiced and not as real as all the interviews turned out. So in this case the

disconnect between the interviewer and interviewee functions in a compelling way.

cannot answer the question the way the interviewer asks it. After the

interviewer rewords it, Derrida gives yet another brilliant answer and makes

the interview a success. If there wasn’t any disconnect it would seem too

practiced and not as real as all the interviews turned out. So in this case the

disconnect between the interviewer and interviewee functions in a compelling way.

A specific part of the film where I connected "Structure, Sign, and Play" was when

Derrida was asked to talk about love and what it means. He connected this concept to love by deconstructing it. The play between love and narcissism is what demonstrates that there is no center.

Derrida was asked to talk about love and what it means. He connected this concept to love by deconstructing it. The play between love and narcissism is what demonstrates that there is no center.

Through Derrida’s film it felt like I got to pick a part a brilliant mind. Listening to

Derrida answer some of the most profound questions really was eye

opening. I especially loved how he said eyes are a part of the body that doesn’t

age and one’s act of seeing has no age. I just think that is such a wonderful

concept that I never thought about yet can relate to. It was really kind of beautiful. The general sense I got out of Derrida’s theories were that they were all collectively thought out and each one of them connect to "Structure, Sign and Play" and ultimately the deconstruction of language.

Derrida answer some of the most profound questions really was eye

opening. I especially loved how he said eyes are a part of the body that doesn’t

age and one’s act of seeing has no age. I just think that is such a wonderful

concept that I never thought about yet can relate to. It was really kind of beautiful. The general sense I got out of Derrida’s theories were that they were all collectively thought out and each one of them connect to "Structure, Sign and Play" and ultimately the deconstruction of language.

Wednesday, October 6, 2010

The Relative Position

Structuralist theory helps us to understand that language is paramount to our existence. In Saussure’s essay, “Course in General Linguistics,” he states that “There are no pre-existing ideas and nothing is distinct before language” (34). Without language, we have nothing. There is no recognition or comprehension of the world without the language necessary to name and compare things to one another, and the terms we use are completely arbitrary.

Saussure goes on to explain that within language, there are three fundamental pieces. The sign (the term we recognize), the signifier (the sound image) and the signified (the mental concept). For example:

Saussure goes on to explain that within language, there are three fundamental pieces. The sign (the term we recognize), the signifier (the sound image) and the signified (the mental concept). For example:

Let us say that a flower, perhaps an orchid, is our sign.

The signifier, or sound-image, is the sounds that form the word orchid.

The signified, or mental concept, is the idea of an orchid and it is unrelated to an actual orchid, but they cannot be separated from one another.

Signs consist of the signified combined with the signifier, and signs constitute language. Without the mental concept of an orchid, and the sound-image of said orchid, we could not recognize the plant as an orchid. We would not recognize it at all. Because language is a system of differences without positive terms, there is no essential value of a sign. If we did not have the sign "orchid" we would understand it in relation to other things around it. An orchid is not a butterfly, and an orchid is also not a dandelion. We can name it as a flower because there are other flowers similar to it, which speaks to another point of Saussure's: signs function not through their intrinsic value but through their relative position.

Signs are given meaning through their position within a structure of differences. Saussure's famous example is of the 8:25 train. It doesn't arrive or depart at 8:25, and perhaps the 8:25 train is a bus, but we still recognize it as the 8:25 train because it comes between the 7:25 and 9:25 trains. Without the 7:25 and 9:25 trains, there would be no point of comparison for the 8:25 train. It is only the 8:25 train because it is not the 7:25 or 9:25 train.

Another example of this could perhaps be given through a paradigmatic chain.

fetus infant toddler child adolescent adult

The shift in title from one stage of development to the next is based upon several things: age, activity, ability, etc. An infant is an infant because they are no longer inside the womb (as a fetus would be) but they cannot do anything for themselves, like walk or begin to speak like a toddler. Likewise, an adolescent is an adolescent because they have gained far more independence than a child, but they are not fully grown and (supposedly) responsible like an adult. Because of differences, we can determine which category a person falls into. There is no value without comparison or exchange. Signs mean nothing without other signs within the same system of language. Outside of the language that signs exist within, they can only have meaning if there is a point of comparison, as explained with Saussure's example of the French mouton with the English mutton and sheep.

The signs we utilize, and their relationships to one another, as well as the relationship between the signified and signifier are arbitrary. Simplistically, you could argue that the word used for one thing could have been used for another thing. The signifier (sound-image) of "orchid" has nothing to do with the plant. The orchid doesn't simply pop out of the ground and say "Hey world, I'm an orchid" (clearly, because orchids are plants and they don't have consciousness and therefore they do not have access to language but that is another story entirely). It could have easily been named potato, cat, gobbeldigook, etc.

In discussing the arbitrary nature of signs, I think of something rather silly. A friend of mine takes issue with the term eggplant. An eggplant, he says, is not shaped like an egg, and it doesn't resemble an egg in any way. He argues that oranges are called oranges, because they're orange, and since eggplants are purple, they should be called purples, and every time he eats eggplant he says "Mmm, that's a mighty delicious purple, it must be prime purple season." As silly and comical as my friend's position on eggplant may be, I am not too quick to discredit it. He has taken an issue with the sign eggplant, and the lack of connection between the sound-image "eggplant" and his mental concept of eggplant. There is no essential value in the term eggplant, and we know eggplants as eggplants because they are not zucchini, and they are not oranges.

As for "The Death of Ferdinand de Saussure" by the Magnetic Fields, the lyric "You can't use a bulldozer to study orchids" deals with the complexity of language. The lyric appears at the end of a verse, which goes as follows:

Love is a concept, and as the song suggests there is little understanding of it and all of it's complexities. "I'm not so sure I even know what it is," illustrates that it is impossible to understand love, and because it is so complex, it is fair to surmise that there are many mental concepts for which love signifies. Love has no intrinsic meaning or value, and therefore cannot have a universal meaning. The complexities of love are supposed to be what makes it beautiful, somewhat like an orchid, and in using a bulldozer to study an orchid you would undoubtedly destroy it, much like assigning a universal meaning to love would destroy it (whatever it is).

The rest of the song goes as follows:

The signs we utilize, and their relationships to one another, as well as the relationship between the signified and signifier are arbitrary. Simplistically, you could argue that the word used for one thing could have been used for another thing. The signifier (sound-image) of "orchid" has nothing to do with the plant. The orchid doesn't simply pop out of the ground and say "Hey world, I'm an orchid" (clearly, because orchids are plants and they don't have consciousness and therefore they do not have access to language but that is another story entirely). It could have easily been named potato, cat, gobbeldigook, etc.

In discussing the arbitrary nature of signs, I think of something rather silly. A friend of mine takes issue with the term eggplant. An eggplant, he says, is not shaped like an egg, and it doesn't resemble an egg in any way. He argues that oranges are called oranges, because they're orange, and since eggplants are purple, they should be called purples, and every time he eats eggplant he says "Mmm, that's a mighty delicious purple, it must be prime purple season." As silly and comical as my friend's position on eggplant may be, I am not too quick to discredit it. He has taken an issue with the sign eggplant, and the lack of connection between the sound-image "eggplant" and his mental concept of eggplant. There is no essential value in the term eggplant, and we know eggplants as eggplants because they are not zucchini, and they are not oranges.

As for "The Death of Ferdinand de Saussure" by the Magnetic Fields, the lyric "You can't use a bulldozer to study orchids" deals with the complexity of language. The lyric appears at the end of a verse, which goes as follows:

I met Ferdinand de Saussure on a night like this

On love, he said, I'm not so sure I even know what it is

No understanding, no closure, it is a nemesis

You can't use a bulldozer to study orchids, he said so

Love is a concept, and as the song suggests there is little understanding of it and all of it's complexities. "I'm not so sure I even know what it is," illustrates that it is impossible to understand love, and because it is so complex, it is fair to surmise that there are many mental concepts for which love signifies. Love has no intrinsic meaning or value, and therefore cannot have a universal meaning. The complexities of love are supposed to be what makes it beautiful, somewhat like an orchid, and in using a bulldozer to study an orchid you would undoubtedly destroy it, much like assigning a universal meaning to love would destroy it (whatever it is).

The rest of the song goes as follows:

We don't know anything

You don't know anything

I don't know anything

About love

And we are nothing

You are nothing

I am nothing

Without love

I'm just a great composer and not a violent man

But I lost my composure and I shot Ferdinand

Crying, it's well and kosher to say you don't understand

But this is for Holland Dozier Holland, his last words were

We don't know anything

You don't know anything

I don't know anything

About love

But we are nothing

You are nothing

I am nothing

Without love

His fading words were

We don't know anything

You don't know anything

I don't know anything

About love

But we are nothing

You are nothing

I am nothing

Without love

The line concerning Holland-Dozier-Holland refers to a Motown songwriting team that often wrote about love, but they didn't provide any sort of meaning. They wrote songs like, "Stop! In the Name of Love!" and "You Can't Hurry Love." Holland-Dozier-Holland wrote about why love hurts so much, and what you have to do to obtain it. Saussure is correct in saying that we know nothing about love, because it is something that can't be understood through language, but the artist may be suggesting that although we know not what it means, we need to embrace that it exists.

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

An Overview of Marx's Economic Theory

Chris Craig’s “Some Thoughts on Ideology” explains some of the ways hegemony and ideology function in a capitalist culture, exploring a few subtle (and some not so subtle) ways in which we, as capitalist subjects, are conditioned to value a system which promotes exploitation and greed above all else. While these examples are certainly valuable insights upon which our understanding of Marxism depends, we thought it might be useful to think about the economic and historical aspects of Marxist theory. One could argue that Marxism in its most basic form is an economic theory, and that understanding the theories of economics it analyzes and promotes is basic to any further application of the theory, be it literary, cultural, or historical.

Central to Marxist economic theory is the commodity and commodity production. In the first chapter of Capital, Marx defines a commodity as “an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another.” The production of commodities depends on two things: first, the existence of a market of exchange, and second, the social division of labor to produce different commodities for exchange. Marx holds that the conditions of this exchange are dependent on the use-value, the actually usefulness of the commodity, and the exchange-value, which is determined by the labor time necessary to produce any given commodity. The exchange value is what is expressed in the price of a commodity. The idea that the labor time required to produce a commodity determines its value is called the labor theory of value, which forms the premise of Marxist economic theory.

Marx argues that capitalism is a distinctive economic system because it not only involves the exchange of commodities, but also the advancement of capital, that is, money or assets that are available for investment. Capital that is ‘left over’ after the costs of production have been met is profit, the accumulation of which is the ultimate goal of capitalism. In order to generate profit, capitalism needs three things—exploitable resources, exploitable labor, and exploitable markets. Clearly, exploitation is a theme here. The capitalist always seeks to get more for less, much in the way a consumer bargain hunts at a sale. In terms of resources, lower prices or more efficient technology can allow the capitalist to pay less for the same quantity and quality of material. Chris mentioned the way that capitalists seek to exploit labor—wage slavery, meaning that the worker must produce surplus value, or value that exceeds the worth of the worker’s effort. On a basic level, this means that the capitalist must get the laborer to do ten hours of work for five hours of pay. Marx argues that it is this exploitation of the laborer that generates profit, an idea known as the surplus value theory of profit. The laborer is exploited from another angle as well, as a consumer in an exploitable market. If capitalists can produce more for less while demand increases, then prices can be set higher, generating further profit. In another way, if capitalists can find new commodities and create demand for them, this will also further profit.

As Chris explains, there are various ways of convincing the laborer and the consumer to participate in a system that exploits them. For the laborer, this means wage slavery. In wage slavery, the capitalist pays the laborer just enough to keep him or her coming back to work and producing, but not enough that he or she is able to take the steps to escape their enslaved position. This works because the laborers do not have capital of their own, thus all they have to sell is their labor. For the consumer in the capitalist market, hegemony and ideology work together to convince an individual to buy those jeans or that ipad. In either case, the capitalist creates conditions which trap the consumer and the laborer in their subservient position.

It is this fact that led Marx to write in the first chapter of the Communist Manifesto that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle.” Marx’s theory of historical materialism, something we spoke about in class, posits that societies progress and decline according to material conditions. That is, the economic base and superstructure’s ability to develop or diminish human productive power. Marx argues that humans are essentially productive beings, and that it is the structure of a society, in terms of economics, legal institutions, and political administration, which determine the degree of this production. It is important to note that Historical Materialism emphasizes the productiveness of the society of a whole, thereby defining this productiveness in terms of interdependent relationships and cooperation. This idea is explained in Marx's Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy, in which he says that "Society does not consist of individuals, but expresses the sum of interrelations, the relations within which these individuals stand." The failure of any society to promote productiveness, then, leads to the decline of that society. Furthermore, Marx suggest that at this point of decline, workers become aware of their subjugation and the alternatives available to, leading them to revolt. Hence, the Communist Manifesto call to arms, “Working men of all countries unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains.”

Marx’s theories of economics and historical materialism have, like all theories, developed over time as new scholars come to understand and interpret them. While many of Marx’s original theories have been altered to account for original gaps in logic or misconceptions generated by the text, the principles discussed here provide an overview of Marxist economic theory which is vital to understanding Marxism as a broader theory. A compilation of Marx’s work is available here. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is also a useful site for getting a general background on many prominent theories, an overview of Marxism can be found here.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Some thoughts on Karlheinz Stockhausen

What does it mean to theorize 9/11 on a political or aesthetic level as something other than "attack" or "terrorist act"?

Both of the terms “attack” and “terrorist act” carry sentimental implications. Both terms also carry negative connotations, thus turning the person or group carrying out the attack/terrorist act into the ‘bad guy’. The receiver of these actions therefore becomes the ‘victim’. To theorize 9/11 as something other than these sentimental ideas is to imply that the theorist does not adhere to the thought that the United States are the ‘good guys’ and al-Qaeda constitute the ‘bad guys’. In turn, this insinuation suggests that whoever doesn’t sympathize with the United States may as well be a terrorist themselves (whatever that means). The jingoism that erupted after 9/11 condemned any action that may have seemed unpatriotic. American flags hung everywhere, not due to some surge of patriotic pride in everybody, but based on the national understanding that the lack of an American flag would be negatively regarded.

What are the aesthetic components of 9/11, according to Stockhausen?

What are the aesthetic components of 9/11, according to Stockhausen?

The events of September 11, 2001 provoked many emotions on the international level; some portions of the world’s population were distraught, shocked, and appalled, others terrified and disturbed, while others felt a sense of satisfaction and perhaps euphoria. This multitude of emotions is precisely what art is supposed to provoke. The artist, while they may desire a certain reaction, has no control over the affect their work has on the viewer, as art is subjective. As a composer, Stockhausen sought to reach people on a completely sensory and emotional level, and he appreciated that the events of 9/11 were able to do this. As an artist, he viewed the amount of preparation and attention to detail executed by the participants in the event, and related it to slaving over a composition noting, ''You have people who are so concentrated on one performance, and then 5,000 people are dispatched into eternity, in a single moment. I couldn't do that. In comparison with that, we're nothing as composers.'' In addition to the overflow of emotion around the world, the victims of 9/11 were forever changed by the event (albeit through death). Art has the potential to change for better or for worse, and whether the change is better or worse is entirely subjective. Stockhausen’s assertion that the events of 9/11 were “the greatest work of art that is possible in the whole cosmos” is not necessarily praise for violence, but instead an appreciation of the effort necessary to orchestrate and produce a pervasive reaction.

How do we define terrorism? How do we define art?

There is no all-encompassing definition for what constitutes art anymore. Through numerous movements, there has always been somebody driven towards the avant-garde. The outbreak of World War I corresponded to the beginnings of an especially revealing art movement, the Dada movement. Dada begs the question, “What is art, and who is in charge of deciding?” Dada brought any presupposed qualifications for art crashing to the ground. Marcel Duchamp’s readymade sculpture Fountain, which premiered in New York City in 1917, galvanized the artistic community and forced its viewers to question their own views on the boundaries imposed on art.

To view Fountain, click here: http://images.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://www.shafe.co.uk/crystal/images/lshafe/Duchamp_Fountain.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.shafe.co.uk/art/Marcel_Duchamp-_Fountain_%28Readymade-_1917%29-.asp&usg=__GCQu30DjDv35Na1gFyrcuG1NKx8=&h=520&w=403&sz=22&hl=en&start=1&sig2=1x3KVoOCLNmYWqlsuoLkyw&zoom=1&tbnid=kWwO-Xe9cLSZnM:&tbnh=131&tbnw=102&ei=5y2WTJW6I8K78gbztbCNDA&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dduchamp%2Bfountain%26hl%3Den%26biw%3D1280%26bih%3D587%26gbv%3D2%26tbs%3Disch:1&itbs=1

To view Fountain, click here: http://images.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://www.shafe.co.uk/crystal/images/lshafe/Duchamp_Fountain.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.shafe.co.uk/art/Marcel_Duchamp-_Fountain_%28Readymade-_1917%29-.asp&usg=__GCQu30DjDv35Na1gFyrcuG1NKx8=&h=520&w=403&sz=22&hl=en&start=1&sig2=1x3KVoOCLNmYWqlsuoLkyw&zoom=1&tbnid=kWwO-Xe9cLSZnM:&tbnh=131&tbnw=102&ei=5y2WTJW6I8K78gbztbCNDA&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dduchamp%2Bfountain%26hl%3Den%26biw%3D1280%26bih%3D587%26gbv%3D2%26tbs%3Disch:1&itbs=1

Duchamp’s Fountain is a urinal rotated 90 degrees and signed “R. Mutt.” The immediate reaction for some may be disgust. Perhaps the viewer would involuntarily visualize somebody using the urinal for its original purpose. Others may simply state, “That’s not art, that’s just a urinal.” Dada answers this dismissal with, “Why isn’t it art?”

Personally, I would suggest that anything (including films, paintings, home furnishings, landscaping, Lego sculptures, literally ANYTHING) that moves one to feel a certain way – terrified, giddy, horny, serene – should be considered art. Whether or not something induces a positive or negative reaction does not matter in the world of art. What is important is that a reaction exists. The most poisonous reaction one could have (not only to art, but to anything in life) is an indifferent reaction. After 9/11, there was a gargantuan reaction worldwide, which is all an artist ever wants for his or her creation. As a composer, Stockhausen is familiar with the artistic strive towards affecting people on an emotional level. On some unconventional level, his remark expresses a degree of jealousy at his inability to affect people as intensely as 9/11 did.

According to Merriam-Webster (available online at http://www.merriam-webster.com/), terrorism is defined as “the systematic use of terror especially as a means of coercion.” The organizers behind 9/11 plausibly fit into this definition; however, so does the schoolyard bully who beats other students up for their lunch money. Angus Martyn’s article “The Right of Self-Defense Under International Law – the Response to the Terrorist Attacks of 11 September” (available at http://www.aph.gov.au/library/Pubs/CIB/2001-02/02cib08.htm#international) addresses this blurry definition, directly stating that the international community has never succeeded in developing an accepted comprehensive definition of terrorism. In 1985, despite the failure to define terrorism, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution “unequivocally condemn[ing], as criminal, all acts, methods and practices of terrorism wherever and by whomever committed...[and calling]s upon all States to fulfill their obligations under international law to refrain from organizing, instigating, assisting or participating in terrorist acts in other States, or acquiescing in activities within their territory directed towards the commission of such acts.” How can one condemn an action fairly without being able to define it?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)